Sharing my work with you - One Story at a Time

Copyright by the author - cannot be reproduced for sale or without permission.

I thought I would like to share some of my stories with visitors. I hope you get something out of these. Let me know if you do.

Tartan Pajamas

Roy McTavish enjoyed his apartment. It was on the lower East End and enviously upscale. He was pleased he could easily afford it. He sauntered across the living room, enjoying the sensation of his shoes sinking into the deep pile carpet, the weave thick and sumptuous. Outside the glass wall situated for a panoramic view, the city steamed in the mid-summer heat. He, however, basked in coolness and comfort. Yes, he had done well for himself. Not that his family had been poor. They had all (as far as he knew) been professional people or well educated, at least. Yet, he was successful beyond them all, and he enjoyed the money it had brought him. Leeza, his wife, had decorated the place herself. She was a whiz. She had even done a couple of the paintings – and all of it stood up to the most critical scrutiny. The apartment was tasteful, yet splashed with beauty and vibrant color. That was Leeza. His glance moved to his collection of African American folk art on the cherry wood shelves he had especially made for it, and a Mona Lisa smile lit his face. This was his pride and joy, as Leeza liked to say. In private, she chided him that these artifacts were his children, since he didn’t seem to want any kids. (She did.)

Leroy Baines McTavish, despite his Scottish name, was a black man. He had always hated his name and had shortened Leroy to “Roy” years ago. He had considered changing his surname - a gross lie in his estimation - to something with African roots, but thus far a suitable substitute had not occurred to him and since his Scottish appendage was the name in which he and his family had accumulated honor and money, he lacked the necessary motivation to seriously pursue this alternative.

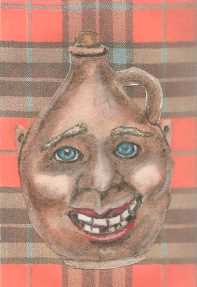

Among his collection of cherished artifacts, sacred to him since they defined his roots and his race, were a few clay pots and jugs. These were perhaps his favorite things, but before today whenever he had assessed his collection, he was always vaguely dissatisfied. This was because there was a hole in it - an empty space on one of the shelves, which, in his vision, could only be filled by the one great thing he still coveted and had not yet succeeded in finding – a “Dave the Slave” face jug. He had first seen Edgefield South Carolina pottery in the early 1980’s and was captured by the quality of workmanship, the glaze and the fact that some of the earlier work was done by slaves – his people. Since that time, he had scoured the market for those done by his favorite maker, “Dave”, a slave known for his large pots with curious rhymes inscribed on their sides. He had one such crock he had found at a reasonable price. He had insured it for a good sum of money, since Dave the Slave’s work was catching on like wildfire and was worth a mint. But then he had heard a rumor that Dave had done a few face jugs, although at that time no one had seemed to know where these jugs were. Roy liked this kind of jug with a face sculpted into its surface and he had face jugs by other potters in his collection, but he was on fire for one of Dave’s. He was sufficiently flush at this time that he could afford it, even though Leeza probably wouldn’t like it, since she still cherished hope that he would change his mind about having a baby.

Dreaming of pottery, he moved toward that available space on the shelf and tenderly ran his hand over the wood, seeing in his mind a wonderful piece of work, one that would evoke the admiration of his friends who also collected such things. Today, however, he did not mope. His eyes gleamed, for today he had hope of acquiring such a gem. The director of the Art Institute had told him that a certain retired judge in the State of North Carolina, a collector of American folk art, had such a jug in his collection. The judge was a white man, yet he collected African American crafts. Hardly fair, Roy thought, as he dreamed of rescuing the jug and placing it in its true milieu – an African American household. All day, he had been stewing in his mind, rehearsing the honeyed, persuasive words he would use in his letter to the judge. He had been warned by the art director that money wouldn’t mean much to the judge. So, he would have to use persuasion … and maybe, even guile. This suited Roy just fine, for this was his forte’. You see, Roy was an advertising man. He had worked his way up in this field with his considerable skills of artifice and enticement and was now an executive with a large company in the big city.

After a quiet dinner with Leeza, during which her gourmet cuisine was lost on him, he carefully crafted a letter, no, a masterpiece, using all his skills and, yes, a dash of guile. It was, he calculated, just the proper blend of courtesy, confidence, and appeal to human compassion that might stir the generosity of a southern judge. Then he drafted a couple of follow-up letters and plotted a strategy to use with possible telephone calls if his first contact didn’t pan out. As part of his long-range strategy he listed everything with which he could possibly “bribe” the judge – choice game tickets (if he was a fan), concert tickets, stock in his company …. He would call in a few favors if he needed to. He even considered the few people he knew who were somewhat famous, thinking the judge might enjoy meeting one of them. At midnight he sighed and went to bed. He hadn’t spent so much effort and thought on a campaign since his coup of the Nabisco account in ‘75.

After two weeks had passed and he still hadn’t had a response, he fretted and had his secretary check out the judge and his address, but he was assured he had made no mistake. So, he was forced to fret awhile longer. At home, his vision rested too often on that empty space on the shelf that would look so fantastic with Dave’s face jug on it, spot lit from above. What should he do? It would soon be three weeks – would that be too early to send a follow-up letter? Would that “southron gentleman” be put off by his pushy Yankee manners? A thrill of horror touched him each time he allowed himself to think that the judge might have already sold the rare jug to someone else. He would not wait an entire month.

Finally, when he was teetering on the brink of mailing the previously prepared follow-up letter, he received the reply at his office. (He had thought he had better use his office address in case Leeza saw his correspondence. He wasn’t ready to tell her about it yet, not until it was in the bag and he knew how much it was going to cost him.) He tore open the envelope and his eyes ate up the contents of the letter as his rapid-fire mind calculated what those polite words really meant.

At first glance, it seemed disappointing but with further reading he decided it was not a lost cause.

The old boy wrote that he owned several face jugs, but that it had been years since he had last examined them, since they were in his cabin in the Smoky Mountains. He had planned to retire to that place, but had not yet done so. He would, he said, have to go and look at them to see if Dave the Slave had actually signed one of them and to decide if he might be willing to part with that particular one. He disdained any reference to money, but wrote that he was very fond of the jugs, himself. Roy assessed every nuance of this letter. The judge hadn’t flat out refused, so he was considering his deal. The question was, would he really go to his cabin and follow up, or would his impulse just die for lack of momentum?

Then Roy noticed the postscript at the bottom of the page:

“Did your ancestors, by any chance, come from Tennessee? There is a McTavish family originally from that State in which I have an interest. McTavish is a fine name, with an illustrious history. My great grandmother was a McTavish.”

Roy’s mind raced. Okay, so he thinks I’m a white man because I have a Scottish name. It wasn’t the first time this had happened. But, this gave Roy the opening he was looking for, so he wasn’t about to tell him otherwise. Besides, wasn’t his great grandfather actually from Tennessee? It was a coincidence that he could use to his advantage. Why shouldn’t he encourage this man’s delusion? It would be only a little “white” lie. He snickered at his own joke and picked up the phone to call his Aunt Maudie. Roy didn’t know much about his ancestry, but, he thought, how different could it be from other Black Americans? …..Slavery, suffering, his ancestors probably whipped and tortured.

Aunt Maudie remembered the place in Tennessee that their first known McTavish had come from. It was a little place in the hills, a hole in the wall, really, called Clarkston. She said she wasn’t even sure that it was still there. Roy discovered he had made a mistake by stirring up her nostalgia and memories because she wanted to go on and on. His mind wandered. Finally, he cut her short by saying he was busy at the office but he promised to call her again from home. He fibbed, saying he was interested in knowing all about the family tree.

(Later, he forgot to call.)

He was thrilled to be able to send another letter to keep the momentum going and to ally himself with the judge, in that southern way of producing possible kinship from the dim and distant past. And who knew? Maybe that tinge of paleness in his forbears came from a plantation owner abusing his female slave. Momentary rage rose within him at the injustice done to his people in the past. But he controlled himself, because he couldn’t let that seep through into his letter. He gracefully slid his way through this communication, expressing gratitude for Judge Walker’s kindness and finally giving the location of his Tennessee forbears as “a little place called Clarkston.” Roy hadn’t been able to locate it on a map, but he was certain it couldn’t be anywhere near where the judge’s people had lived and this farce would end there. But still, this laughable, possible kinship had been a fortuitous opening for a continuing dialogue. After writing and re-writing, He mailed this hopeful missive, resisting the foolish impulse to kiss the envelope as he placed it in the outgoing mail.

He realized he was obsessing over this jug and had to cool down. But somehow he had really gotten into it. Playing the judge like a fish had enhanced the challenge all the more.

This time, the response came much sooner. Roy had been very busy and picked up his mail as he was leaving the office. Warning himself that he would remain cool whatever the contents, he waited until he was home. There, with admirable restraint, he made himself comfortable and settled down with a cool drink before opening the envelope.

First, the judge indicated he would soon be off to the mountains for his summer retreat and would examine the jugs then. Well, it was very frustrating to find out that he hadn’t already done so, but that part seemed hopeful. And he didn’t say he wouldn’t sell the jug. But there was no more about that, for the formerly reticent judge seemed excited about the McTavish lineage. His sentences bristled with exclamation marks. His great grandmother’s McTavish ancestors had been from Clarkston! Imagine that! What a remarkable coincidence that had made their paths cross in this way! Then he went on and on about the McTavish Clan history, their grandeur and valor. “You can be proud,” he boasted, “of being a McTavish.” Roy was startled for a moment; then he whooped aloud. Leeza, strolling through the living room, wanted to know what was so funny. He paused. “Oh, this silly white man yearning for his Scottish roots. He thinks he and I must be related because his great grandma was a McTavish from Tennessee. Then he read to her the part about the bravery of the McTavish Scots and said acidly, “He probably dresses up in a kilt every year for a Scottish festival… maybe even plays the bagpipe… and he thinks I’m related to him. He doesn’t know I’m black.”

She shrugged, “Well, just tell him.”

“Uh, well, I don’t want to do that just yet.” He scrunched further down into his chair.

He had to tell her then, why he had to cozy up to this man, had to glad-hand him the way southerners did before they felt comfortable enough to do business.

Had to confess that he wanted to buy a face jug that cost as much as a new car.

Then she was angry, the worst kind of angry, like she got only once in a while. She was stone cold silent and simply left the room. He sat there alone; compressed by the chill she had left behind. That was worse than when she blew up at him. And he was uneasy, too, because he saw there could be danger in stringing the judge along any further, yet he yearned for that face jug. He went back to the letter, his mind busy with its contents.

But wasn’t it odd, that the judge had relatives in Clarkston – that tiny place.

Maybe his family owned my family, he thought.

“Aw man. That’s it. His people used to own my people and now I’m suckin’ up to this old guy to buy something from him that a slave made for the white folks in South Carolina. ….Weird.”

He sighed, “Well, this jug, if he parts with it, is probably going to cost me plenty. I guess I can console myself that I, a black man, can afford to buy it.”

The expense made his mind turn to Leeza, wondering how he could schmooze her into a good mood. It wouldn’t be easy. Leeza was a hard sell, for she was strangely unmoved by the things most women wanted. Jewelry and that kind of thing wouldn’t do it. Leeza really only wanted one thing – a baby and time off from work to immerse herself in motherhood. He knew they didn’t really need her salary now. Yet, he was proud of her and her career, her independence, her classy looks. He just couldn’t see her as a housewife, taking care of diapers and bottles. Why she wanted to do it was beyond him…. But maybe if he held out a mild suggestion that he might reconsider this as a possibility, she might be civil to him again. He wouldn’t have to make a definite decision. He could change his mind again later. He sagged deeper into his chair, feeling a little low.

He had to work to arouse his former enthusiasm for this pursuit of the face jug.

This third letter to the judge was like walking on eggshells - congenial but non-committal. He really didn’t see how they could be related, he stated, but who knew? He pretended to be enthusiastic about this possibility but wove a little truth in, admitting that he knew very little about his family’s past and nothing at all about Clan MacTavish. He continued in the guise of a possible relative, asking questions about the judge’s other interests, hinting at friendly favors that he might be able to offer him and tactfully asking about his favor, the jug, only at the end of his letter. He read it over, assessing the result of his machinations. It appeared just the right combination of gentleness, grave politeness, good old boy comradeship and appeal to the judge’s sense of duty and honor. Still, he was firmly letting the old guy know that he was waiting to hear about the jug. His skillful language wove a net of gauzy guilt to snare the judge’s conscience if he neglected to respond in a timely manner, with the desired result. It wasn’t easy to achieve this kind of psychological vise on a gentleman of the old school, but it could be done and Roy thought he knew how to do it. He used his home address this time, since the jig was up with Leeza.

It was a full month before he heard from Judge Walker again. As he waited, Roy, entangled in this tantalizing game, was at first anxious, wondering if he should he prod the old fool again and was tempted to write another letter, this time addressing him as “cousin.” His anxiety soon passed into frustration while he fretted about why the judge didn’t get off his backside and go to that North Carolina cabin. Finally, after three weeks, he slid into stoic, pretended apathy. He was reluctant to telephone, because he had a feeling he might come across as a con man, too eager. And, once trapped in conversation, he might have to say too much. He might have to confess his race. He knew he was much better with the written language and would not have to say any more than he had to in a carefully composed letter.

When he had just about given up, the third letter came - enclosed, curiously, within a small package.

Roy was relieved. It turned out that the judge had been sick with pneumonia. While recuperating in bed, he wrote, he had been going over old family memorabilia again. It had revived his interest in historical memoirs and McTavish family lore. He was, he said, sending along with this letter a small token of, if not their relationship, at least friendship. Roy’s previous hints of favors he might be able to do for the judge were ignored. To his great dismay, nothing more was said about the jug, although he knew he could scarcely expect the judge to drag himself from his sickbed to go on such an errand. That is, if he really had been sick at all.

What could he possibly be sending him?

When he moved the tissue wrapping beneath the letter, he saw it was something made of loud plaid flannel. He pulled this out and shook it. Pajamas! ….. It was pajamas! Red, blue and black plaid PJs, with, of all things, a black Scotty dog in a tam-o’-shanter sewn onto the shirt pocket. A dangling tag announced that the plaid was that of Clan McTavish. Roy’s mouth hung open as he stared at this thing that was so alien to him that it hurt his eyes. It was a minute or so before he could believe what he saw, before his mind could assimilate the implications. This was too much – it was totally ridiculous! He hesitated between laughter and despair. What now? What should be the next move in his brilliant scheme? He paced for awhile, angry with the judge who seemed to insist that he must belong to Clan McTavish before he could negotiate for the jug. It was revolting. He had put up with his crazy name all his life, but by God he would not even pretend to embrace a Scottish clan, even for a Dave the slave face jug.

That night he had Leeza take a picture of him in those ludicrous pajamas. She laughed so much it was difficult to get a still shot, but the resulting digital image was amazing. Taken by the light of the flash, his dark skin contrasted weirdly against the gaudy plaid, his teeth gleaming whitely as he grimaced into the camera. Then he jotted a terse note to the judge. He was sorry, he said, for the misunderstanding. He had decided it was unnecessary to say anything else – the time for teasing, toying, psychology and seduction was over. The photo said it all. This whole face jug experience had been bad for him, had made him obsessive, and he was giving it up.

(Yet even as he thought this, it still hurt a little.)

But he was angry, too. He had a sneaking suspicion that old Judge Walker had never had any intention of parting with the jug. He believed that he was a devious old man, stringing him along all the time.

When his weak and whispering conscience asked if he hadn’t done the same to the judge, his fury only mounted.

Well, it didn’t matter anyway, because even if his calculation was wrong and the judge was honestly considering selling the jug, when he found out that he was black and not one of his kinfolk, he certainly wouldn’t. Well, that was just too bad, wasn’t it? By God, he was African American and he wasn’t ashamed of his race. He threw the tartan pajamas into a corner of his den. For some reason, he couldn’t just throw them into the trash. He was repelled and fascinated with them at the same time. He couldn’t quite let go of the whole frustrating experience. Deep down, he had a faint hunch that this strange business might not be over yet.

The next day he made a special trip to the post office to mail his final letter. When he came home again, he began thinking about his own roots, his family. He thought maybe he would call Aunt Maudie again. But then he forgot, again.

After sending the photo, Roy McTavish gave his life over to other things, and the face jug incident began to submerge within his file of memories labeled “strange.” Thus, he was surprised when he received another small package from Judge Walker – this time, a brown envelope full of papers. Warily, he settled down to read the accompanying letter, expecting a verbal thrashing for his impudence in misrepresenting himself. Instead he was startled, because if a letter could crow, this one would have. Judge Walker was clearly exuberant. “I hardly know where to begin – You will understand my reluctance up until now to disclose this story to you until I could be sure of the details of your ancestry and your race. As I told you, I have been through all the family papers. Now I am sure that you should know the facts and that you should have the enclosed documents. I will leave this discovery to you, for when you read these letters from Dr. Angus McTavish (or “Doctor Mac” as he was called) to my great grandmother, you will understand all.

Roy’s initial aversion turned to avid curiosity. Beneath the letter, there were some photocopied papers with a label clipped to them that read: “Letters from Dr. McTavish of Clarkston Tennessee to his sister, Martha Walker of Topeka Kansas.”

The handwriting was flowery, written in the distant past when handwriting was an art form, and was faint in some places so that it was difficult to read.

Jan’y 22, 1871

Elmwood Grove, Clarkston, Tennessee

Dearest Martha,

Yes, I received the woolen cloths you sent me and they will be much appreciated by my young patients who have the croup this winter. Influenza took several of my patients last season. I do the best that I can but most of them are very poor and they dislike to send for me until it is almost too late to do anything for their condition.

I could not live in the city, dear sister. I am better where I am needed. My thanks to you for asking and I know that Carl would welcome me like a brother. Besides, I have the boy now. You will remember I wrote to you about him. His mother died last winter here in my cabin. You would not remember her. She came into this area a few years ago after you married Carl and moved away. When she felt well enough, she sometimes came here to do laundry for me and cooked my meals when I was at home. In this way, she paid for her medicine. I didn’t know what to do about the boy, so I took him in until things could be sorted out. The county came here to take him off to the poor house in Memphis. You see, he had no relations to take him in and they rightly said he could not live alone. I don’t know how they heard about him away out here, but I suspect they have some kind of pact with the officials there in Memphis to keep them supplied with free workers. But I prevented it by telling them a bald-faced lie. You will doubtless be very surprised because you know I have never been able to tell a lie, but I did so like I was born to it that day. I am even proud of it. When you read this, you will either cringe or laugh and I wish I could be there to see which. Well, Martha, I declared to them that I was the boy’s father. Yes, I really did. I said it without so much as blinking an eye. I stared them down while their jaws dropped and their eyes popped and I didn’t budge a whisker.

I can’t say they believed me, especially as the boy has no hint of my red hair and ruddy skin, but they could not prove it was not so. I even told them I would give them certification as a doctor that he was my son and that I had waited on his mother at his birth. Even that was not true, for the poor woman never would have summoned a doctor. You will remember that the few Negroes here and poor white women nearly always have a woman come in and help with such things. Sometimes with tragic results.

Well, the upshot is that I am now the father of a Negro boy of, as near as I can tell, eight years of age. You can be assured it took no time at all for the tale to circulate in Clarkston. Everywhere I have gone since, all turn to stare at me as though I am a freak show. They have not said anything and I do not wonder. I am the only doctor for many miles and I have served them well, taking trade or service in kind for my skill in keeping them alive. They do not want to disturb my peace too much or I may leave. Besides that, I believe they know the boy is not really mine. This is such a small place that they may know his origins better than I. No doubt they believe I am quite eccentric, but they are willing to put up with it. There have been stranger things, even in Clarkston. You see, I know their secrets, too

The boy has entered my heart, Martha. I don’t know what I thought would happen, and indeed I did not think beyond saving the boy from that Memphis hellhole, but he has sneaked up on me and claimed me as his own. He follows me around and makes calls with me, no matter what the weather. I have to bundle him up and see that he is not exposed to infection, but I cannot leave him alone at home for any lengthy time. Somehow he has made himself believe that I truly am his father. He prodded me one evening as we sat by the fire, hinting for some assurance that I had truly claimed him as my son. I said something to the effect that I needed a son, that I was tired of being an old bachelor and that he and I would have to look after each other. His great brown eyes glowed in the firelight and my heart turned over. I can’t describe the look he wore, but I can tell you, Martha, I will never turn this boy away. He then asked me many questions about fathers and sons and I could tell that he still needed some assurance of my commitment to him. Thinking a symbol of some kind was necessary; I looked through my paltry trinkets and found a token from my medical school days. This I bored a hole through and strung it with a leather cord. We had a little ceremony of laying this around his neck and thus endowed with legitimacy, he seems very satisfied. Now sister, don’t laugh too much. Indeed, think of our pitiful plight in Scotland and how glad we were to come with our mother and father to this country. Every heart needs a true home to rest in, and his now has my humble abode and my protection. I hope I can continue to do well by him, but the feeling against his race is strong now after the war. However, you know Clarkston never was much for the war and as hill people they were ignorant about slavery. I shall have to remain here or move to the north, for he would not be so well received elsewhere. Oh, his name, by the way, is Benjamin. Benjamin McTavish - Tisn’t it a good Scottish name?

Well, Martha, I must close for now for I am drugged with sleep and must find my bed. I send my love to Carl and the children. If you find some of that Red Heart elixir you might send it.

Your loving brother, Angus

Noting that the letters were in chronological order, Roy continued to read. He was so hooked now that no one could have torn the papers from his hands.

June 3, 1872

Elmwood Grove

Clarkston, Tennessee

Dearest Martha,

I am so glad we have each other to write to since the loss of our dear parents. We have always understood one another, haven’t we? I am pleased to hear you have named your new infant after myself and only hope that I can lay down footsteps worthy of him to follow. I am but a country doctor yet I hope I am doing a bit of good in this world. Kiss him for me and tell him I pray for him daily, as I do for all your children and of course for you and Carl as well.

To answer the questions in your last letter – Yes, Mary, Benjamin’s mother confided to me that his father had been a “blue coat” – a Union soldier. You understand Martha that she was not at all a “light woman” and I did not ask her questions about this private and possibly painful matter. Many unfortunate things happened during the war. I believe his father must have been a white man, since Benjamin is of lighter skin than his mother. I do not know, nor does he, if his father is still alive, but it matters not at all since I do not believe he would ever claim him. It is his loss, for the boy is good through and through and very bright besides. He is a great help to me in the house and has learned to be a tolerable cook. Which brings me to one of those tangles you asked about in my adventure of raising a black boy as my own. Whenever I am on a call at a homestead and mealtime arrives while I am there, the mistress or master of the house will ask that I stay to partake with them. This is actually considered by some to pay at least a part of my fee. Sometimes it is possum or coon with sweet potatoes and I have yet to be able to stomach such, but no matter. The south is indeed poverty stricken now and we must all scavenge the land for our sustenance. To return to the problem, I must explain that at home Ben and I take our meals together as a natural course and I must say I never gave any thought otherwise until the first such event arose. I had finished the delivery of Mrs. Schmidt. She has six children now and has become an old hand at it, hardly needing me there. Her older daughter has learned the arts of housewifery and I had noticed the savory odors emanating from their kitchen. Mr. Schmidt politely inquired if I might stay for supper. None of us had eaten dinner and we were all famished. I readily assented but when I came to the table and found there was no chair placed for Benjamin I realized my mistake. Now Martha, you have always claimed that I have my wits about me, and I must admit this time I did so. I suddenly remembered that I must clean my instruments and therefore suggested they eat before us, setting a place for myself and for “my boy” when they were through. This they did and it reveals something of the politeness and reserve of the people of this region that the word got round and ever since that event all have fallen into this scheme whereby we are all made comfortable. At those times when I must stay the night in the home of my patient, Benjamin sleeps nearby. We must both take whatever bed can be made up then - a blanket on the floor is quite enough. Other than the eating arrangements there have been few problems such as you suggested in your letter. However, when we traveled to Memphis, it was a different story. It began when Benjamin pointed out to me that the seat of my second best pants was worn quite thin and that if I didn’t take care I would soon be in an embarrassing position. I decided I could delay a trip to the city no longer so we set out. I selected a room that suited my small funds and had a cot brought in for Benjamin. We bought our food and brought it there to eat. I thought all was well, but I was ignorant. It was amazing Martha, the difference between the country and the town. It seemed we could not walk anywhere, shop in any store, without some slight being directed to this poor small boy. I can tell you, I was awakened to the facts you mentioned in your last letter. I began to notice when we were in a place of business that Ben soon learnt not to draw attention to himself by standing by my side but would find himself a place where he would be little noticed. He trailed behind me as we walked on the street. He looked pale and hurt. We had finished with the tailor and walked out into the street when Benjamin tripped on a loose board in the walk and fell forward, saving himself by snatching at a man’s coat. The fellow wasn’t hurt in the slightest, but he was irate that my boy had fallen against him and Benjamin had just finished a peppermint so that his hands were a bit sticky and left a spot on the man’s lapel. I was about to apologize and offer to pay something for the cleaning of his coat, but the fellow raised such a rumpus with his name-calling that I became quite angry myself and was actually thinking of teaching him a lesson in manners. I fancy I still have the brawn of my fist-fighting youth. But just then I became aware that others had stopped and were staring at us so I took Benjamin’s hand and we returned to our room, with me steaming all the way. I realized we could not stay as long as I had planned and we left soon after. He was quiet all the way back home and even though we had a talk on the subject, he is not quite the same. I wish we had never gone to Memphis.

I know, Martha, that you are thinking that once more my soft heart has gotten me into trouble, but I am alone in the world and the boy has been a joy to me and I know that he is very fond of me.

(Here the doctor began to regale his sister with tales of the country people he lived among - “hillbillies”, thought Roy – and he skimmed over that.)

My love to you as always,

Angus

Noting that the next letter was dated more than two years later, Roy read on:

December 20, 1874

Elmwood Grove

Clarkston, Tennessee

My Dear Martha,

You must stop worrying about me so. All is well here and Benjamin and I look forward to the birthday of our Lord. You will be glad to hear I have not neglected his Christian education. You know I have never had much patience with some of the books of the Old Testament, but I have often told him to follow the pattern of Christ in his life and he will not go wrong. I am sending with this letter some presents for your children. Ben and I have stayed late by the fire to finish the jumping jacks and the cornhusk doll was made by a neighbor. Ben wanted to send you a note which is enclosed herewith.

I regret I was unable to make the journey to meet with you at Carl’s family home in Atlanta, but I believe you will understand my reluctance to leave my patients in the worst of winter months. I know you are disappointed but hope you will forgive me in time. We have several inches of snow here now but are snug in our little cabin.

Love as always,

Angus

Roy knew right away that Angus McTavish’s reason for not traveling to Atlanta had little to do with his patients. Had his sister really thought he would leave Benjamin at home alone, or did she imagine he would take him with him to Atlanta? At the bottom of this letter, in a remarkably good hand for an eleven-year-old child, thought Roy, were these few lines:

Mistress Martha,

I thank you for allowing me to write to you. We are to make snow cream after we finish wrapping your package. My father tells me you and he were used to making snow cream when you were children together. He says you and he had many happy times together. It must be a very pleasant thing to have a sister. I hope your children enjoy what we are sending. I do not know them, but I am sure they must be good children to have such a mother. Please give them love from Ben.

This was followed by a letter with a few spots, probably drops of water, spreading the ink here and there into amoeba-like formations.

March 31, 1875

Elmwood Grove

Clarkston, Tennessee

My dear sister,

My heart is greatly saddened by your great loss. The parting from a child of such a young age must be a most grievous one to bear. Rest assured he is in the arms of Jesus. After casting round in my mind I can think of no solace to offer you except to bring your attention to your other four children, healthy and strong, who will give you grandchildren in your old age. You ask if there was anything different that I would have done. No, heart of my heart, I verily believe your doctor did all that could have been expected of him. Perhaps it was time for your small angel to leave you for a better place. We cannot understand death, perhaps, but we know life continues elsewhere. I know some do not truly believe this, but I have seen dying faces illumined with a glow that could only have come from Heaven. Do not grieve, for in time you and I will see little Angus on the other side.

As for me, I am well enough and glad to be alive. I contracted a fever and lingering cough, but Benjamin nursed me through it, God bless him! I could not have done better myself. He has learned many of my tricks and studies my books. I believe he has resolved to be a doctor and nothing would please me better. I must look into where he might go to be trained and do my best to save for it. I have a bad habit of neglecting to collect my fees. I now see I must make a better effort to do so. It would not be justice to him if he could not be schooled for a proper career. I know he has the intelligence and wisdom to pursue such if he so desires. I must admit I worry about his future, for I hear that the Negro is no more accepted as an equal in the north than in the south. He seems not to have been harmed much by word or deed here in Clarkston, but I have kept him under my wing. I know he would benefit by the company of other children, but this, you understand, is not possible with my work. Nor do I want to see him hurt. He plays sometimes with the children of the families I tend to, but this is not frequent. I have undertaken his schooling and acquired such books as are necessary from New England. I am pleased with his progress as it seems to me that he could hold his own with any white boy of his age. I know many would be scandalized at such a statement and perhaps I am not a fair judge of the matter, but I have observed other children and have inquired of their fathers and their teachers as to the proper studies to be undertaken. I was thinking, Martha, that you might ask your friends in New Haven if they have any views regarding the best course to educate a Negro boy with the medical profession in mind. Would there be a future for him in New York or Chicago, do you think? You were good to offer to find a place for him with that Negro family in Kansas, where he would have both father and mother and sisters, but he has decided and I believe it best that we go on as we are.

As for the liniment Carl is using, I do not think it can harm him at all. I will try to send him a bottle of my own making that I believe he may benefit from as soon as I am able. I have sent for camphorated oil and Ben and I have gathered fresh herbs, roots and bark of late. He knows the names of all and is fast learning the use for them.

Your loving brother through thick and thin,

Angus

I am sending you a photograph of myself and the boy. It was taken some time ago, and he and I have both grown a bit since then – he in the vertical plane, myself in the horizontal. Yet we are happy enough in our abode and glad the winter is fading away and spring coming soon.

(Roy looked, but didn’t see any picture. He went on reading)

July 17, 1877

Elmwood Grove

Clarkston, Tennessee

Dear Martha,

I am greatly saddened by your last letter. You must know that I love you and would see you if I could. I do not like to be away from here for the length of time it would take to make the journey to Topeka, to visit a while and then return, even though the train does make such a trip possible. However, I have discussed this with Benjamin and he believes he will be quite capable of taking care of things here at home, so perhaps I shall. I would prefer that he come with me but I can see the difficulties that would place upon you. Oh, Martha! How is it that we can acknowledge the love of Christ for all, yet hold back from the embrace of a black child. I confess I do not understand why your friends would not understand that I acted solely from compassion when I took Benjamin in to live with me and that I have been blessed many times for it. For I can tell you, Martha, that he is no different than your children must be. He has a fine, upright bearing, is well educated and intelligent and has a most compassionate heart. As for his speech, Martha, there you are mistaken. Although he was a bit difficult to understand at first, being shy and mumbling, he now speaks quite clearly and has the use of words far beyond his age. I am told he sounds like me, so I suppose he is a Scotsman after all. He has acquired some small skills of surgery and medicine. I believe this has been good for his position here. He assists me in mixing draughts and tinctures and knows his herbs. The word has got round that he acts as my assistant and he has been called to look at an ankle to see if it was broken or only sprained and a sick child to determine if she had a dangerous fever and on these occasions, he acquitted himself quite well. I am proud of him, Martha. I believe he will become a fine doctor if I can give him his final education. I have been saving for this for some time and if I can do without new shoes for another winter, I will do so. I can scarcely afford the trip to your home, but if Carl is set upon sending me the fare, I will see you in September. I dare not wait later than that, for otherwise we may have ice on the ground before I return.

Love, Angus

The next letter was dated only a couple of months after the last one. It was evident that Angus had not gone to Kansas, after all.

September 22, 1877

Elmwood Grove

Clarkston, Tennessee

My Dear Martha,

How can you have misunderstood so? Or, I should say, how can you have changed so much from the girl I remember, the girl with such compassion for all those who were bullied, the girl who nursed and cared for injured animals. How can you pretend I would insult Lizzy or your fine sons? Nevertheless, I now know I cannot come. I shall not ask for your help in any venture that involves my boy, my son. I close this letter with the prayer that you will see your error and know your brother as he is and has always been.

I still send my love as ever,

Angus

Roy was amazed. How could Angus have been so naïve? Yet, he was moved by the sincerity within the man’s words, and angered by the stupid and arrogant Martha, who had been upset by the Doctor’s proud comparison of his black son to her precious children.

The next letter, the last one of the lot, was in a different hand. It was a very refined, small script as though the writer was meticulous and well educated.

It was headed:

Chicago, Illinois

January 14, 1902

To Mrs. Martha Walker, Walker’s Station, Topeka, Kansas

Madam –

With great grief, I write to inform you of the death on December 13 last of your brother, Angus Roy McTavish. Although he had not been in contact with you for some years past, I assure you he had not forgotten his beloved sister and your estrangement from him was a lingering heartache.

I believe you should know how much he is missed in Clarkston and that entire region of Tennessee. So many gathered for his funeral that the church could not hold them all and although it was bitterly cold, many mourners stood outside the door in the snow, determined as they were to show proper respect for this man who had loved and cared for them all these many years.

I say loved, because he was remarkable in that aspect. Although many of his patients could not afford to pay him his fee and some thought him not respectable in the eyes of society, still he loved them. Through the years that he was among them they fully learned his character and valued him as a man above most men, forgiving and loving all without judgment of any kind. Thus he was loved in return by many. No one loved him more than I, who owe him more than I can adequately express to you. Where would I be now, had it not been for the love of this man I was allowed to call “father?” Who else would have done for me what he did? Besides his love he educated me far above the usual station of one of my race, but more importantly he taught me loyalty and devotion surpassing that of any other man I have ever known. He often used to jest with me about my McTavish name and “heritage” saying a good Scotsman was brave, loyal and devoted to those he loved. He also said that by Christ’s example, we should learn to love unstintingly, everlastingly and that we would never want if we followed that path, for the joy that came from such a life would be reward enough. I have found his teaching to be true, although it has been difficult for me at times. Still, I will always remember his example and will try to keep the McTavish name unblemished in honor of this great man, my white father, to whom love was a way of life.

Sincerely,

Dr.Benjamin McTavish

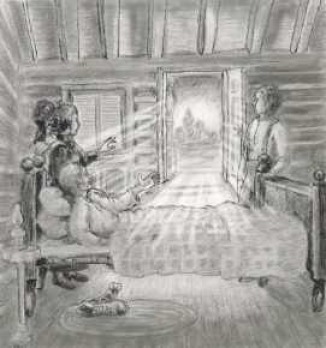

Beneath this last letter, there was another item, carefully wrapped and reinforced with cardboard. Roy slit the tape and a picture slid out into his hand - a very old, cracked photograph. It was a picture of a burly man, bearded and robust, one hand gripping a medical satchel, the other arm around the shoulder of a small black boy holding the reins of a buggy. The paper folded over the photo bore this inscription in Judge Walker’s handwriting: Doctor Angus McTavish and his Negro “son”. If you look closely you will see that the boy is wearing around his neck the amulet that McTavish gave him as proof of his “adoption”.

Roy stared closely at the picture in the light of the lamp. He was stunned, for he remembered now, that, years ago, he had received such a medal from Aunt Maudie. It had come from his grandfather’s estate. He galloped to his bedroom and rummaged through the box that had accumulated all his junk – loose buttons, old coins and the like. Guilt stricken, he finally found it - tangled up with some old cuff links and a tie bar. In the bottom of the box he found the note his Aunt Maudie had enclosed with this thing, stating: “Our ancestor, Benjamin McTavish received this medal from his doctor father. He cherished it all his life and it has been handed down in the family ever since.” At the time, Roy hadn’t known who this Benjamin McTavish was. He had assumed he was his great grandfather, for that was the point in time at which his knowledge of his family tree fell away into oblivion. But this had to be at least a generation further back in time. He took the medal into the light. It was a caduceus – a serpent on a staff - the symbol of those in the medical profession. Well, he had heard that someone in the family had been a doctor – sent to school by his father, also a doctor. But that was all. Never in his wildest dreams would he have imagined such a history, such a life. Certainly nothing had ever been said about his great, great grandfather having a white father.

He spent a long time in the den, sunk deep in his thoughts.

Leeza gaped at him. “Why in the world are you wearing that?” she said, when Roy wandered into their bedroom wearing the plaid pajamas. “Its a cold world, baby”, was all he said as he climbed in beside her. Then, he reached over and stroked her cheek before he rolled over in the bed. He lay there in the dark in the fetal position considering the strange vagaries of life. Just when you thought you had things figured out, it changed and you didn’t know where you were or who you were. He felt like a child again, seeking security. But the Scotsman’s plaid flannel was warm and comforting like the words and love of big Angus McTavish and Roy’s heart glowed with pride in his great, great grandfather, Doctor Benjamin. Two such men could make at least a small change in the world, one that could extend over generations. This last thought gave him peace and he fell asleep in it.

He woke early. Leeza stirred sleepily and he pulled her into his arms. She lay quietly on his chest as he told her about the letters. By the time he had finished, she was quietly weeping, dampening his plaid pajama shirt.

Then he surprised even himself, because what came out of his mouth then came directly from his heart, bypassing his analytical ad man brain. “Baby, you know, I think we ought to go ahead and have that baby now.” She looked up at him, amazed and speechless. “Yeah, well, I don’t know how good a father I will be, but you’ll surely be a great mom…. And he - or she - will have some awfully interesting McTavish ancestors.” Then they laughed as though this was the funniest joke in the world. Their lovemaking that followed was so fine, so exultant that Leeza was convinced that this first “unprotected” time would be the one that did it. She teased him about his sexy pajamas. They were potent, she said, and vowed to keep them ready for future occasions that might warrant their use.

Of course, he telephoned Judge Walker to thank him for his gift. He wanted to hear his voice, to make closer contact with this man who was from the same blood as Doctor Angus McTavish. They talked a long time. Roy was not disappointed with the real man, and was glad.

The face jug arrived shortly after. He had not mentioned it to the judge again and other things had taken over his attention, so he could hardly believe the contents of the crate that had been delivered so carefully. Enclosed with it was a bill, modest for such a valuable object, and a note in which Judge Walker addressed him as his “cousin by courtesy”. Roy unwrapped the jug with anticipation, his eyes shining as he gloated over the marvelous black face it depicted - the wide lips, the bulging, comical eyes. Then he turned it around to search for the mark of its maker and was startled, for there on the other side of this two-handled jug was yet another face, staring up at him. But this face was different…. It was white, blue-eyed, thin-lipped – and laughing, it appeared, at the amazement on Roy’s own face. Then he noticed the inscription incised into the jug by the potter. It rambled down the side of jar and around the base, where it was signed with the name of its maker, “Dave.” Roy held it to the light. The rhyme was typical of Dave the slave - crude and cryptic:

“Black or white we cannot know –

when to this world we come

and out we go.”

Leroy Baines McTavish, despite his Scottish name, was a black man. He had always hated his name and had shortened Leroy to “Roy” years ago. He had considered changing his surname - a gross lie in his estimation - to something with African roots, but thus far a suitable substitute had not occurred to him and since his Scottish appendage was the name in which he and his family had accumulated honor and money, he lacked the necessary motivation to seriously pursue this alternative.

Among his collection of cherished artifacts, sacred to him since they defined his roots and his race, were a few clay pots and jugs. These were perhaps his favorite things, but before today whenever he had assessed his collection, he was always vaguely dissatisfied. This was because there was a hole in it - an empty space on one of the shelves, which, in his vision, could only be filled by the one great thing he still coveted and had not yet succeeded in finding – a “Dave the Slave” face jug. He had first seen Edgefield South Carolina pottery in the early 1980’s and was captured by the quality of workmanship, the glaze and the fact that some of the earlier work was done by slaves – his people. Since that time, he had scoured the market for those done by his favorite maker, “Dave”, a slave known for his large pots with curious rhymes inscribed on their sides. He had one such crock he had found at a reasonable price. He had insured it for a good sum of money, since Dave the Slave’s work was catching on like wildfire and was worth a mint. But then he had heard a rumor that Dave had done a few face jugs, although at that time no one had seemed to know where these jugs were. Roy liked this kind of jug with a face sculpted into its surface and he had face jugs by other potters in his collection, but he was on fire for one of Dave’s. He was sufficiently flush at this time that he could afford it, even though Leeza probably wouldn’t like it, since she still cherished hope that he would change his mind about having a baby.

Dreaming of pottery, he moved toward that available space on the shelf and tenderly ran his hand over the wood, seeing in his mind a wonderful piece of work, one that would evoke the admiration of his friends who also collected such things. Today, however, he did not mope. His eyes gleamed, for today he had hope of acquiring such a gem. The director of the Art Institute had told him that a certain retired judge in the State of North Carolina, a collector of American folk art, had such a jug in his collection. The judge was a white man, yet he collected African American crafts. Hardly fair, Roy thought, as he dreamed of rescuing the jug and placing it in its true milieu – an African American household. All day, he had been stewing in his mind, rehearsing the honeyed, persuasive words he would use in his letter to the judge. He had been warned by the art director that money wouldn’t mean much to the judge. So, he would have to use persuasion … and maybe, even guile. This suited Roy just fine, for this was his forte’. You see, Roy was an advertising man. He had worked his way up in this field with his considerable skills of artifice and enticement and was now an executive with a large company in the big city.

After a quiet dinner with Leeza, during which her gourmet cuisine was lost on him, he carefully crafted a letter, no, a masterpiece, using all his skills and, yes, a dash of guile. It was, he calculated, just the proper blend of courtesy, confidence, and appeal to human compassion that might stir the generosity of a southern judge. Then he drafted a couple of follow-up letters and plotted a strategy to use with possible telephone calls if his first contact didn’t pan out. As part of his long-range strategy he listed everything with which he could possibly “bribe” the judge – choice game tickets (if he was a fan), concert tickets, stock in his company …. He would call in a few favors if he needed to. He even considered the few people he knew who were somewhat famous, thinking the judge might enjoy meeting one of them. At midnight he sighed and went to bed. He hadn’t spent so much effort and thought on a campaign since his coup of the Nabisco account in ‘75.

After two weeks had passed and he still hadn’t had a response, he fretted and had his secretary check out the judge and his address, but he was assured he had made no mistake. So, he was forced to fret awhile longer. At home, his vision rested too often on that empty space on the shelf that would look so fantastic with Dave’s face jug on it, spot lit from above. What should he do? It would soon be three weeks – would that be too early to send a follow-up letter? Would that “southron gentleman” be put off by his pushy Yankee manners? A thrill of horror touched him each time he allowed himself to think that the judge might have already sold the rare jug to someone else. He would not wait an entire month.

Finally, when he was teetering on the brink of mailing the previously prepared follow-up letter, he received the reply at his office. (He had thought he had better use his office address in case Leeza saw his correspondence. He wasn’t ready to tell her about it yet, not until it was in the bag and he knew how much it was going to cost him.) He tore open the envelope and his eyes ate up the contents of the letter as his rapid-fire mind calculated what those polite words really meant.

At first glance, it seemed disappointing but with further reading he decided it was not a lost cause.

The old boy wrote that he owned several face jugs, but that it had been years since he had last examined them, since they were in his cabin in the Smoky Mountains. He had planned to retire to that place, but had not yet done so. He would, he said, have to go and look at them to see if Dave the Slave had actually signed one of them and to decide if he might be willing to part with that particular one. He disdained any reference to money, but wrote that he was very fond of the jugs, himself. Roy assessed every nuance of this letter. The judge hadn’t flat out refused, so he was considering his deal. The question was, would he really go to his cabin and follow up, or would his impulse just die for lack of momentum?

Then Roy noticed the postscript at the bottom of the page:

“Did your ancestors, by any chance, come from Tennessee? There is a McTavish family originally from that State in which I have an interest. McTavish is a fine name, with an illustrious history. My great grandmother was a McTavish.”

Roy’s mind raced. Okay, so he thinks I’m a white man because I have a Scottish name. It wasn’t the first time this had happened. But, this gave Roy the opening he was looking for, so he wasn’t about to tell him otherwise. Besides, wasn’t his great grandfather actually from Tennessee? It was a coincidence that he could use to his advantage. Why shouldn’t he encourage this man’s delusion? It would be only a little “white” lie. He snickered at his own joke and picked up the phone to call his Aunt Maudie. Roy didn’t know much about his ancestry, but, he thought, how different could it be from other Black Americans? …..Slavery, suffering, his ancestors probably whipped and tortured.

Aunt Maudie remembered the place in Tennessee that their first known McTavish had come from. It was a little place in the hills, a hole in the wall, really, called Clarkston. She said she wasn’t even sure that it was still there. Roy discovered he had made a mistake by stirring up her nostalgia and memories because she wanted to go on and on. His mind wandered. Finally, he cut her short by saying he was busy at the office but he promised to call her again from home. He fibbed, saying he was interested in knowing all about the family tree.

(Later, he forgot to call.)

He was thrilled to be able to send another letter to keep the momentum going and to ally himself with the judge, in that southern way of producing possible kinship from the dim and distant past. And who knew? Maybe that tinge of paleness in his forbears came from a plantation owner abusing his female slave. Momentary rage rose within him at the injustice done to his people in the past. But he controlled himself, because he couldn’t let that seep through into his letter. He gracefully slid his way through this communication, expressing gratitude for Judge Walker’s kindness and finally giving the location of his Tennessee forbears as “a little place called Clarkston.” Roy hadn’t been able to locate it on a map, but he was certain it couldn’t be anywhere near where the judge’s people had lived and this farce would end there. But still, this laughable, possible kinship had been a fortuitous opening for a continuing dialogue. After writing and re-writing, He mailed this hopeful missive, resisting the foolish impulse to kiss the envelope as he placed it in the outgoing mail.

He realized he was obsessing over this jug and had to cool down. But somehow he had really gotten into it. Playing the judge like a fish had enhanced the challenge all the more.

This time, the response came much sooner. Roy had been very busy and picked up his mail as he was leaving the office. Warning himself that he would remain cool whatever the contents, he waited until he was home. There, with admirable restraint, he made himself comfortable and settled down with a cool drink before opening the envelope.

First, the judge indicated he would soon be off to the mountains for his summer retreat and would examine the jugs then. Well, it was very frustrating to find out that he hadn’t already done so, but that part seemed hopeful. And he didn’t say he wouldn’t sell the jug. But there was no more about that, for the formerly reticent judge seemed excited about the McTavish lineage. His sentences bristled with exclamation marks. His great grandmother’s McTavish ancestors had been from Clarkston! Imagine that! What a remarkable coincidence that had made their paths cross in this way! Then he went on and on about the McTavish Clan history, their grandeur and valor. “You can be proud,” he boasted, “of being a McTavish.” Roy was startled for a moment; then he whooped aloud. Leeza, strolling through the living room, wanted to know what was so funny. He paused. “Oh, this silly white man yearning for his Scottish roots. He thinks he and I must be related because his great grandma was a McTavish from Tennessee. Then he read to her the part about the bravery of the McTavish Scots and said acidly, “He probably dresses up in a kilt every year for a Scottish festival… maybe even plays the bagpipe… and he thinks I’m related to him. He doesn’t know I’m black.”

She shrugged, “Well, just tell him.”

“Uh, well, I don’t want to do that just yet.” He scrunched further down into his chair.

He had to tell her then, why he had to cozy up to this man, had to glad-hand him the way southerners did before they felt comfortable enough to do business.

Had to confess that he wanted to buy a face jug that cost as much as a new car.

Then she was angry, the worst kind of angry, like she got only once in a while. She was stone cold silent and simply left the room. He sat there alone; compressed by the chill she had left behind. That was worse than when she blew up at him. And he was uneasy, too, because he saw there could be danger in stringing the judge along any further, yet he yearned for that face jug. He went back to the letter, his mind busy with its contents.

But wasn’t it odd, that the judge had relatives in Clarkston – that tiny place.

Maybe his family owned my family, he thought.

“Aw man. That’s it. His people used to own my people and now I’m suckin’ up to this old guy to buy something from him that a slave made for the white folks in South Carolina. ….Weird.”

He sighed, “Well, this jug, if he parts with it, is probably going to cost me plenty. I guess I can console myself that I, a black man, can afford to buy it.”

The expense made his mind turn to Leeza, wondering how he could schmooze her into a good mood. It wouldn’t be easy. Leeza was a hard sell, for she was strangely unmoved by the things most women wanted. Jewelry and that kind of thing wouldn’t do it. Leeza really only wanted one thing – a baby and time off from work to immerse herself in motherhood. He knew they didn’t really need her salary now. Yet, he was proud of her and her career, her independence, her classy looks. He just couldn’t see her as a housewife, taking care of diapers and bottles. Why she wanted to do it was beyond him…. But maybe if he held out a mild suggestion that he might reconsider this as a possibility, she might be civil to him again. He wouldn’t have to make a definite decision. He could change his mind again later. He sagged deeper into his chair, feeling a little low.

He had to work to arouse his former enthusiasm for this pursuit of the face jug.

This third letter to the judge was like walking on eggshells - congenial but non-committal. He really didn’t see how they could be related, he stated, but who knew? He pretended to be enthusiastic about this possibility but wove a little truth in, admitting that he knew very little about his family’s past and nothing at all about Clan MacTavish. He continued in the guise of a possible relative, asking questions about the judge’s other interests, hinting at friendly favors that he might be able to offer him and tactfully asking about his favor, the jug, only at the end of his letter. He read it over, assessing the result of his machinations. It appeared just the right combination of gentleness, grave politeness, good old boy comradeship and appeal to the judge’s sense of duty and honor. Still, he was firmly letting the old guy know that he was waiting to hear about the jug. His skillful language wove a net of gauzy guilt to snare the judge’s conscience if he neglected to respond in a timely manner, with the desired result. It wasn’t easy to achieve this kind of psychological vise on a gentleman of the old school, but it could be done and Roy thought he knew how to do it. He used his home address this time, since the jig was up with Leeza.

It was a full month before he heard from Judge Walker again. As he waited, Roy, entangled in this tantalizing game, was at first anxious, wondering if he should he prod the old fool again and was tempted to write another letter, this time addressing him as “cousin.” His anxiety soon passed into frustration while he fretted about why the judge didn’t get off his backside and go to that North Carolina cabin. Finally, after three weeks, he slid into stoic, pretended apathy. He was reluctant to telephone, because he had a feeling he might come across as a con man, too eager. And, once trapped in conversation, he might have to say too much. He might have to confess his race. He knew he was much better with the written language and would not have to say any more than he had to in a carefully composed letter.

When he had just about given up, the third letter came - enclosed, curiously, within a small package.

Roy was relieved. It turned out that the judge had been sick with pneumonia. While recuperating in bed, he wrote, he had been going over old family memorabilia again. It had revived his interest in historical memoirs and McTavish family lore. He was, he said, sending along with this letter a small token of, if not their relationship, at least friendship. Roy’s previous hints of favors he might be able to do for the judge were ignored. To his great dismay, nothing more was said about the jug, although he knew he could scarcely expect the judge to drag himself from his sickbed to go on such an errand. That is, if he really had been sick at all.

What could he possibly be sending him?

When he moved the tissue wrapping beneath the letter, he saw it was something made of loud plaid flannel. He pulled this out and shook it. Pajamas! ….. It was pajamas! Red, blue and black plaid PJs, with, of all things, a black Scotty dog in a tam-o’-shanter sewn onto the shirt pocket. A dangling tag announced that the plaid was that of Clan McTavish. Roy’s mouth hung open as he stared at this thing that was so alien to him that it hurt his eyes. It was a minute or so before he could believe what he saw, before his mind could assimilate the implications. This was too much – it was totally ridiculous! He hesitated between laughter and despair. What now? What should be the next move in his brilliant scheme? He paced for awhile, angry with the judge who seemed to insist that he must belong to Clan McTavish before he could negotiate for the jug. It was revolting. He had put up with his crazy name all his life, but by God he would not even pretend to embrace a Scottish clan, even for a Dave the slave face jug.

That night he had Leeza take a picture of him in those ludicrous pajamas. She laughed so much it was difficult to get a still shot, but the resulting digital image was amazing. Taken by the light of the flash, his dark skin contrasted weirdly against the gaudy plaid, his teeth gleaming whitely as he grimaced into the camera. Then he jotted a terse note to the judge. He was sorry, he said, for the misunderstanding. He had decided it was unnecessary to say anything else – the time for teasing, toying, psychology and seduction was over. The photo said it all. This whole face jug experience had been bad for him, had made him obsessive, and he was giving it up.

(Yet even as he thought this, it still hurt a little.)

But he was angry, too. He had a sneaking suspicion that old Judge Walker had never had any intention of parting with the jug. He believed that he was a devious old man, stringing him along all the time.

When his weak and whispering conscience asked if he hadn’t done the same to the judge, his fury only mounted.

Well, it didn’t matter anyway, because even if his calculation was wrong and the judge was honestly considering selling the jug, when he found out that he was black and not one of his kinfolk, he certainly wouldn’t. Well, that was just too bad, wasn’t it? By God, he was African American and he wasn’t ashamed of his race. He threw the tartan pajamas into a corner of his den. For some reason, he couldn’t just throw them into the trash. He was repelled and fascinated with them at the same time. He couldn’t quite let go of the whole frustrating experience. Deep down, he had a faint hunch that this strange business might not be over yet.

The next day he made a special trip to the post office to mail his final letter. When he came home again, he began thinking about his own roots, his family. He thought maybe he would call Aunt Maudie again. But then he forgot, again.

After sending the photo, Roy McTavish gave his life over to other things, and the face jug incident began to submerge within his file of memories labeled “strange.” Thus, he was surprised when he received another small package from Judge Walker – this time, a brown envelope full of papers. Warily, he settled down to read the accompanying letter, expecting a verbal thrashing for his impudence in misrepresenting himself. Instead he was startled, because if a letter could crow, this one would have. Judge Walker was clearly exuberant. “I hardly know where to begin – You will understand my reluctance up until now to disclose this story to you until I could be sure of the details of your ancestry and your race. As I told you, I have been through all the family papers. Now I am sure that you should know the facts and that you should have the enclosed documents. I will leave this discovery to you, for when you read these letters from Dr. Angus McTavish (or “Doctor Mac” as he was called) to my great grandmother, you will understand all.

Roy’s initial aversion turned to avid curiosity. Beneath the letter, there were some photocopied papers with a label clipped to them that read: “Letters from Dr. McTavish of Clarkston Tennessee to his sister, Martha Walker of Topeka Kansas.”

The handwriting was flowery, written in the distant past when handwriting was an art form, and was faint in some places so that it was difficult to read.

Jan’y 22, 1871

Elmwood Grove, Clarkston, Tennessee

Dearest Martha,

Yes, I received the woolen cloths you sent me and they will be much appreciated by my young patients who have the croup this winter. Influenza took several of my patients last season. I do the best that I can but most of them are very poor and they dislike to send for me until it is almost too late to do anything for their condition.

I could not live in the city, dear sister. I am better where I am needed. My thanks to you for asking and I know that Carl would welcome me like a brother. Besides, I have the boy now. You will remember I wrote to you about him. His mother died last winter here in my cabin. You would not remember her. She came into this area a few years ago after you married Carl and moved away. When she felt well enough, she sometimes came here to do laundry for me and cooked my meals when I was at home. In this way, she paid for her medicine. I didn’t know what to do about the boy, so I took him in until things could be sorted out. The county came here to take him off to the poor house in Memphis. You see, he had no relations to take him in and they rightly said he could not live alone. I don’t know how they heard about him away out here, but I suspect they have some kind of pact with the officials there in Memphis to keep them supplied with free workers. But I prevented it by telling them a bald-faced lie. You will doubtless be very surprised because you know I have never been able to tell a lie, but I did so like I was born to it that day. I am even proud of it. When you read this, you will either cringe or laugh and I wish I could be there to see which. Well, Martha, I declared to them that I was the boy’s father. Yes, I really did. I said it without so much as blinking an eye. I stared them down while their jaws dropped and their eyes popped and I didn’t budge a whisker.

I can’t say they believed me, especially as the boy has no hint of my red hair and ruddy skin, but they could not prove it was not so. I even told them I would give them certification as a doctor that he was my son and that I had waited on his mother at his birth. Even that was not true, for the poor woman never would have summoned a doctor. You will remember that the few Negroes here and poor white women nearly always have a woman come in and help with such things. Sometimes with tragic results.

Well, the upshot is that I am now the father of a Negro boy of, as near as I can tell, eight years of age. You can be assured it took no time at all for the tale to circulate in Clarkston. Everywhere I have gone since, all turn to stare at me as though I am a freak show. They have not said anything and I do not wonder. I am the only doctor for many miles and I have served them well, taking trade or service in kind for my skill in keeping them alive. They do not want to disturb my peace too much or I may leave. Besides that, I believe they know the boy is not really mine. This is such a small place that they may know his origins better than I. No doubt they believe I am quite eccentric, but they are willing to put up with it. There have been stranger things, even in Clarkston. You see, I know their secrets, too

The boy has entered my heart, Martha. I don’t know what I thought would happen, and indeed I did not think beyond saving the boy from that Memphis hellhole, but he has sneaked up on me and claimed me as his own. He follows me around and makes calls with me, no matter what the weather. I have to bundle him up and see that he is not exposed to infection, but I cannot leave him alone at home for any lengthy time. Somehow he has made himself believe that I truly am his father. He prodded me one evening as we sat by the fire, hinting for some assurance that I had truly claimed him as my son. I said something to the effect that I needed a son, that I was tired of being an old bachelor and that he and I would have to look after each other. His great brown eyes glowed in the firelight and my heart turned over. I can’t describe the look he wore, but I can tell you, Martha, I will never turn this boy away. He then asked me many questions about fathers and sons and I could tell that he still needed some assurance of my commitment to him. Thinking a symbol of some kind was necessary; I looked through my paltry trinkets and found a token from my medical school days. This I bored a hole through and strung it with a leather cord. We had a little ceremony of laying this around his neck and thus endowed with legitimacy, he seems very satisfied. Now sister, don’t laugh too much. Indeed, think of our pitiful plight in Scotland and how glad we were to come with our mother and father to this country. Every heart needs a true home to rest in, and his now has my humble abode and my protection. I hope I can continue to do well by him, but the feeling against his race is strong now after the war. However, you know Clarkston never was much for the war and as hill people they were ignorant about slavery. I shall have to remain here or move to the north, for he would not be so well received elsewhere. Oh, his name, by the way, is Benjamin. Benjamin McTavish - Tisn’t it a good Scottish name?

Well, Martha, I must close for now for I am drugged with sleep and must find my bed. I send my love to Carl and the children. If you find some of that Red Heart elixir you might send it.

Your loving brother, Angus

Noting that the letters were in chronological order, Roy continued to read. He was so hooked now that no one could have torn the papers from his hands.

June 3, 1872

Elmwood Grove

Clarkston, Tennessee

Dearest Martha,

I am so glad we have each other to write to since the loss of our dear parents. We have always understood one another, haven’t we? I am pleased to hear you have named your new infant after myself and only hope that I can lay down footsteps worthy of him to follow. I am but a country doctor yet I hope I am doing a bit of good in this world. Kiss him for me and tell him I pray for him daily, as I do for all your children and of course for you and Carl as well.